Lost Bagnigge

With a map of central London fixed over a dartboard, if you were to launch a handful of darts at the board, for as long as you were hitting the board you’d be hitting a spot with multifarious history; every geographic puncture marking a location where the social strata is as varied and transformed as the landscape itself. Taking up a dart, I’m aiming for a treble twenty. Score!

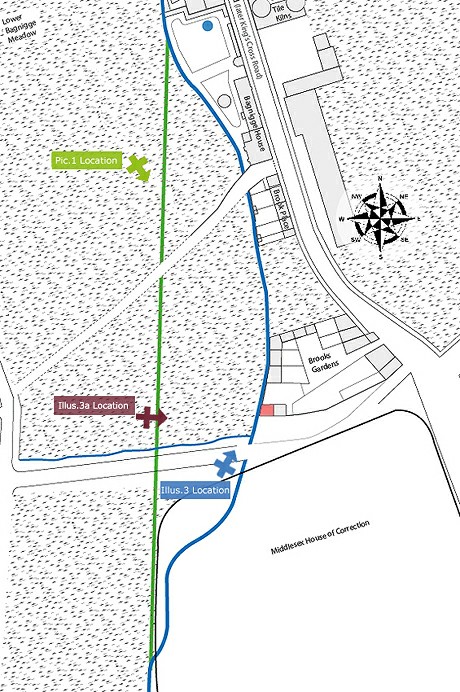

The junction of Pakenham Street and Cubitt Street in St.Pancras is an unremarkable spot. If you were not familiar with the location and were to be instantaneously transported there, you would no doubt be at a loss to your whereabouts, beyond perhaps a guess at the region of the country. It could be any number of suburbs, in any number of UK cities, despite being just one and and half miles by road from the absolute tourist centre of the nation. Of course the instantaneous transporting idea is blown out of the water by street signs and a plethora of local authority dustbins dotted about the place, but you see what I’m getting at; in ice cream terms this street is definitely vanilla. Fig.1 below shows a simple map of the present junction, with markers to indicate the locations of Pic.1 and 2.

The most gushing partisan of London’s tourist board would struggle to drive much traffic to this locality. Today the only thing luring visiting parties to the neighbourhood is a pair of monstrous modern hotels that overlook the scene. Two hundred and fifty years previous however, c.1760, both tourists and locals alike wouldn’t have needed any cajoling to make swift passage to the spot. This commonplace street junction stands thirty yards from what was the main entrance to one of the most popular leisure sites of Georgian London. For its eighty five years as a place of public resort ‘Bagnigge Wells Spa/Tea Gardens’ was the primary draw in a region of other comparable attractions. The spot caught my attention by virtue of being another significant landmark along the course of the River Fleet, later to become the Fleet Sewer, which at different times flowed both alongside and through the gardens of the Bagnigge Wells site.

Prior to its entire route being referenced as the River Fleet there was many a moniker attributed to the watercourse as it meandered from one district to the next. In this locale Stow (A survey of London, 1598) acknowledges the title of The River of Wells, from a charter of William the Conqueror, in 1068; for a time it was also known as the “River Bagnigge”(1). Preceding any development of the site, various names and descriptions of the plot and its general vicinity give an indication of its nature; this “watery or oozy district”(2), formerly known as “Bagnigge Wash, used to be frequently overflowed, when the Fleet Sewer was swollen by heavy rains”(3). Also known as “Bagnigge Marsh”(4) it was referenced in an early grant of land as “a parcel of the waste”(5) of the Manor.

In 1665 when this first recorded land transaction took place it seems reasonable to describe the spot as a quaggy, undeveloped strip of land which formed part of the river’s flood plain, covering approx one acre in a rural setting at the periphery of the City. Pic.2 below gives an impression of how it may have appeared looking north from the point marked on the Fig.1 (thanks to Jon Combe for use of his River Arun picture). The Fleet there through was about twelve feet in width and would have been relatively unpolluted in comparison to its lower reaches. During the time of the first tenants, “George Touffie and his Wife Grace”(6), two properties were built on the site. Presumably at least one of these would have been erected by instruction of Mr Touffie, while the other was perhaps undertaken by a leaseholder to Mr Touffie. Of the two properties, one was known as Bagnigge House, built c.1680, and was to later form part of the Bagnigge Wells resort. The fate of both river and resort were intertwined from the moment the first dwellings were inhabited.

Pic.2 – A representation of the Fleet’s flood plain at Bagnigge Wells c.1660.

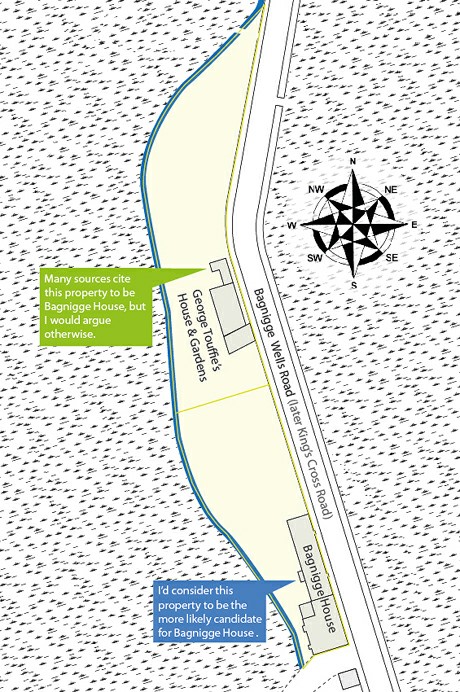

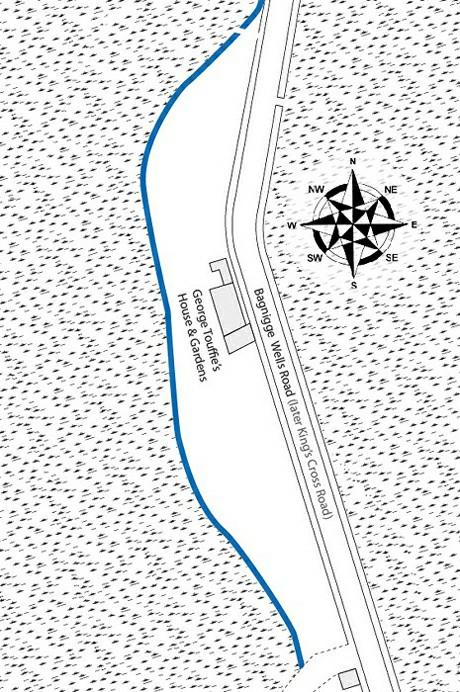

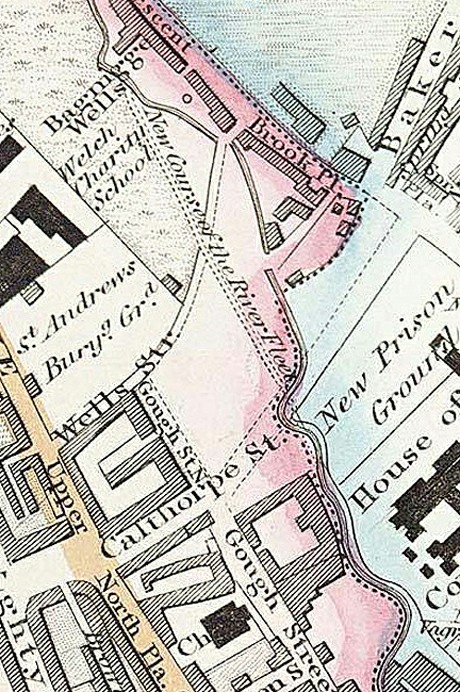

The uncertainty alluded to above, as to which of the two properties was Bagnigge House, is only conjecture on my part. Popular opinion cites the more northerly of the two (see fig.2 below) to be Bagnigge House, but I would argue otherwise. Contemporary etchings and other 18th and early 19th century portrayals of the Bagnigge Wells site clearly show the southern property forming a significant part of the resort; the northern property when shown is outside the bounds of the gardens. Logic would suggest that by the build date of Bagnigge House, fifteen years posterior to the original exchange of land, Mr Touffie would have already established his household, making Bagnigge House the second property to be built. Assuming the southern property to be Bagnigge House, if you consider the site previous to its construction, with only the northern house upon it (fig.3) its position fronting the road roughly in the centre of the plot perhaps supports the argument a little. Further support for the southern property is found in the fact that the wells which were to bring the site to public attention are documented as being located within the grounds of Bagnigge House. Given an accurate geographic location for the wells from various sources, such as the ‘Experimental enquiry’ of John Bevis M.D., and transferring this to 18th century maps e.g. John Rocque’s 1746 map of London, Westminster & Southwark, the wells are found to be very much within the bounds of the southern property. In addition a short descriptive text in Volume 1 of ‘London, past and Present’ (Wheatley 1891) cites Bagnigge House as being “a mansion adjoining the Wells on the south”(7), and again considering the position of the wells and wells site, this supports the case for the southern property.

Fig. 2 – The plot c.1680 featuring both properties.

Fig. 3 – The plot featuring the earliest property.

Between 1680 and 1757 little of consequence is heard of concerning Bagnigge House or the ground which it occupies, being one third of Mr. Touffie’s one acre site. It is known from records that it was transferred in 1701 to a Mr William Clarkson, and of course over the passage of seventy seven years the City without had continued to extend in all directions, encroaching upon its rural surrounds. In 1757 when the house and land once more changed hands, passing to Mr Thomas Hughes, the locality was dotted with some small collections of newer properties, but remained very much a rural setting. The City’s northern boundary closest thereto was 0.3 miles as the crow flies; on foot, taking the shortest route via road and pathway, it was a ten minute walk of approx half a mile. Mr.Hughes, then occupying Bagnigge House, sought advise from an associate concerning waters drawn from wells in the garden, as they seemed to be ineffectual in nurturing his flowers. Considering this enquiry is noted to have been in the same year that Mr.Hughes took on the property, 1757, it seems likely that the wells were already existent on the site. John Bevis M.D., to whom Mr.Hughes’ enquiry was directed, confirms this in the text of his ‘Experimental enquiry’ in which he states that “a late proprietor, upon taking possession of the estate, found two wells thereon, both steaned in a workmanlike manner; but when, or for what purpose, they were sunk, he is entirely ignorant.”(8).

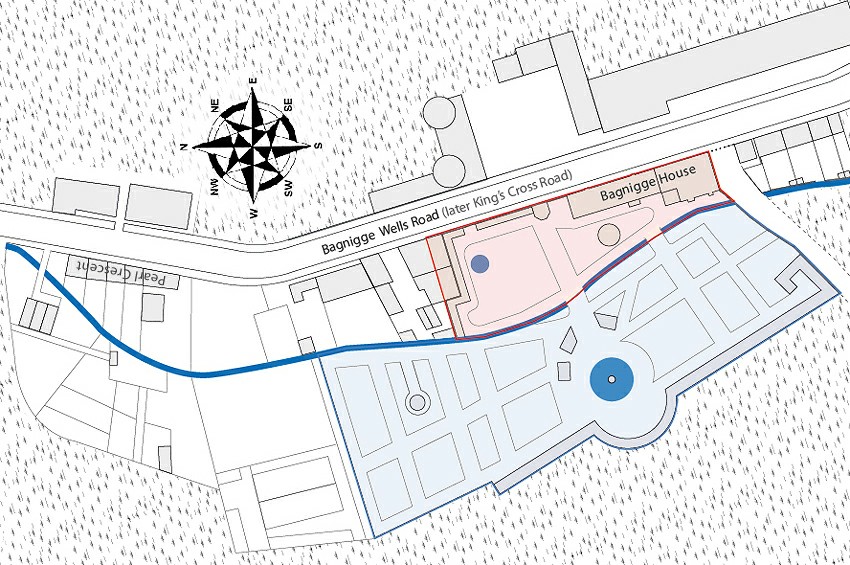

Dr.Bevis’ initial results confirmed his suspicions, that the waters were sourced from mineral springs; consequently Mr.Hughes abandoned his flora in favour of enterprise. A re-modelling of the gardens saw them opened to the public as a spa in 1759 under the name of ‘Bagnigge Wells’, or ‘The Royal Bagnigge Wells’ as an advertisement of 1775 heralds them. The royal connection alluded to by this name most likely concerns the spurious and widely disqualified belief that Bagnigge House was once the residence of Eleanor Gwynn, mistress of King Charles II. The waters at Bagnigge Wells were dispensed by pump for drinking, in view of their purported medicinal properties, sanctioned by the authority of Dr.Bevis’ study. As the resort grew in popularity Mr.Hughes was swift to capitalise, with the addition of entertainment, serving hot buttered loaves, cakes, tea and a variety of stronger brews. These changes soon saw Bagnigge Wells became known more so as a Tea Garden than a legitimate venture for effecting any health benefits to its patrons, although those of infirmity did frequent the resort on weekday mornings to take the waters. Within some short years, in 1762, Mr.Hughes leased the gardens to Mr John Davis who continued to expand upon its amenities. In particular Mr.Davis more than tripled the size of the gardens when he leased land on the western bank of the Fleet/Bagnigge River. These new gardens were laid out in a more formal manner while the original gardens remained rather more rustic. Fig.4 below represents the area c.1800, with the original garden’s perimeter in red and the extended boundary marked in blue shows the addition of the newly leased portion of the brick field of Daniel Harrison. With the river now running through the middle of the resort it was necessary to install bridges to unite the two parts, these wooden bridges themselves added further attraction and points of interest.

Fig. 4 – Bagnigge Wells resort c.1800 with formal gardens west of the river.

In those early days the river played no small part in beautifying the whole scene. Lush vegetation adorned its banks, dappled sunlight broke through the canopy of overhanging willows and sparkled on the water, wrens and dunnocks flitted in and out of their green hiding spots, while the sounds of flowing waters tickled the ears of the brew quaffing grandiose. The river also facilitated another particularly avant-garde arrangement, that sent rather different sounds echoing through the gardens. At the northern end of the eastern gardens a water-wheel was in place in the flow of the Fleet, “as this water wheel turned, connecting rods driven by a crank, pumped air using bellows, and drove the barrel assembly”(9) of an organ which would play on weekday afternoons. Through all this development, the domed and columned pump house, the clipped-hedge lined walkways, leaden statues, fish ponds, fountains, the castellated grotto, the tea boxes; despite all this, the old nature of the district had only been veiled and the resort was still at the mercy of the Fleet. In 1768 a particularly heavy rainfall overflowed the reservoirs of Hampstead, whose waters were filled from the sources of the Fleet, the low-lying gardens of Bagnigge Wells were inundated and left under four feet of water. Similar extreme flood incident occurred in 1809 and 1846 and no doubt on a smaller scale flooding was a frequent occurrence. For as long as the the river was unmanaged and untamed, it would be an ever present threat to livelihoods and residents along its course.

For the entire life of the resort the river was a designated public sewer. Though our present day interpretation may consider this unthinkable, until 1815 it was illegal to connect household sanitary waste to a public sewer, rather each house had a cesspit or other waste store which would supposedly be emptied periodically. So an open sewer at that time wouldn’t be quite what we might imagine, being primarily a land drainage channel, although the laws regarding household waste were often flaunted.

Following the death of Mr. Davis in 1793 the resort came under the management of various lessees for comparatively short periods of time. By the close of the eighteenth century and into the first decade of the nineteenth Bagnigge Wells had somewhat fallen from favour with the people of fashion. This likely wasn’t helped by the reputation of Bagnigge Wells Road thereabouts, which had since the early days of the gardens been a notorious hotspot for thieves and robbers, known to frequent a local pub by the name of the Fox at Bay. As the fashionable elite began to frequent the gardens less and less its patronage shifted, to encompass those seeking less salubrious pleasures. Reflecting its shifting customer base the southern extremity of Bagnigge House had seen the addition of a new building for exclusive use as a public house, though still affiliated with the gardens. What had once been some few houses dotted about the district had developed into regimented streets, and the newly built Middlesex House of Correction occupied a vast site just five hundred feet south of the gardens, where previously had stood a mountainous rubbish heap. All this development was bringing the City’s northern boundary ever closer and on all other sides green fields were being built upon and Bagnigge Wells’ rural setting was much reduced, to more of a rural pocket amidst brick and stucco terraces. As a result of the increase in the population and the frequent disregard for the law concerning use of public sewers, an inevitable increase in the pollution level of the River Fleet through the gardens was seen. In 1813 the lease of the premises changed hands again, and this would mark the beginning of the end for Bagnigge Wells.

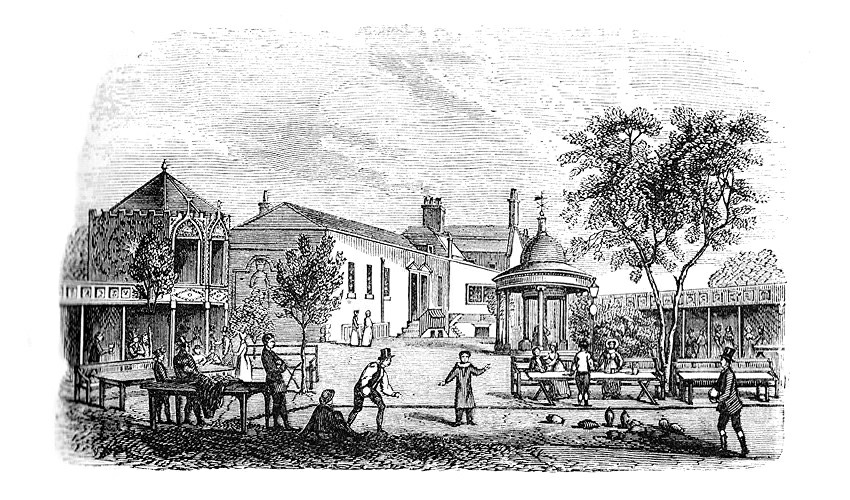

The northern extent of the original land plot, granted to Mr. Touffie in 1665, that had never formed part of the wells site was by 1813 an established terrace of ordered housing, named Pearl Crescent. Between Pearl Crescent and Bagnigge Wells’ eastern gardens was sited a brewery, which would appear to have been part converted from Mr. Touffie’s original property. The houses of Pearl Crescent adjoined the pathway along Bagnigge Wells Road at their front, and the western boundaries of their rear gardens and yards were defined by the River Fleet which was still entirely open. Similarly the brewery’s eastern and western boundaries were defined by the roadway on the east and the river on the west. Mr. Thomas Salter, the new lessee of the wells, had taken on the resort in a period of considerable change, but the most significant of these changes to concern Bagnigge Wells would be as a direct result of Mr. Salter’s tenancy. In the same year that he took on the resort, 1813, he was declared bankrupt resulting in a general sale by auction of the property and all its fixtures and fittings. The greatest consequence of the sale was the loss of the western gardens; for although the property was purchased and re-opened, it was now reduced to its original proportions, previous to the lease of the western lying brick field. Illustration.1 below, from William Pink’s History of Clerkenwell (1881. pp.567), shows the eastern gardens around this period. Looking south towards Bagnigge House in the background, the two storey castellated building on the far left is the grotto and the collonaded circular structure in the centre mid-ground is the pump house from where the waters were drawn. On the far right we can see tea boxes/bays running along the rivers eastern bank, also seen far left tea boxes are adjoined to the boundary wall along Bagnigge Road.

Illus. 1 – Bagnigge Wells, the eastern gardens, looking south. The river would be on the right, out of frame.

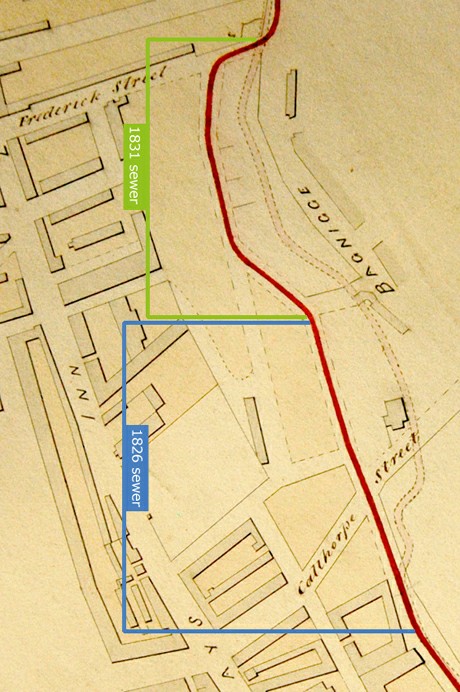

While Bagnigge Wells’ future continued to look bleak the laws concerning public sewers were being relaxed, in 1815 it became legal to discharge household waste to public sewers and soon afterwards there came the first rumblings of public complaint concerning the condition of the river/sewer. The increased pollution, as a result of population growth in the immediate vicinity of Bagnigge Wells, was compounded by similar scenarios along its course yet further upstream in Battlebridge, Kentish Town and Hampstead. Instances of flooding were still common in the low lying valley of Bagnigge Wells Road, but now the floods raised a new concern. In addition to the previous nuisance and threat to property and livelihood, the rivers’ waters carried a much increased threat of disease. In 1825 the Holborn and Finsbury Commission of sewers began to arch over sections of the course of the river through their districts, as circumstance demanded. The first major work undertaken was a 900ft diversion of the river’s course, to create a new line of covered sewer; starting from a point on the river close to the northern boundary of the Bagnigge Wells site and running south to the western boundary of the House of Correction. This section was the first to receive attention for various reasons. The main reason was that the ground above the new sewer was “intended to become a public street or road”(10). The green cross on Fig.5 below marks the same location as that of Fig.1, indicating the spot from where Pic.1 was taken. The route of the 900ft diversion channel is marked(green) on Fig.5, when compared to Fig.1 we can see that the ‘intended public street’ was built, and became Pakenham Street. Conveniently the work coincided with a required diversion of a portion of the river as a result of the expansion of the Middlesex House of Correction. Fig.5 also shows how part of the original course of the river meandered across the north west corner of the proposed new perimeter wall(black) of the prison. These two petitions opportunely allowed for improvement of the drainage of this perpetually marshy locale, and addressed the above mentioned flooding nuisances to a degree, with the lion’s share of the costs being footed by third parties. The property tinted red on Fig.5 provides a reference point for the orientation of Illus.3 & 3a below.

Fig.5 – Development south of the resort.

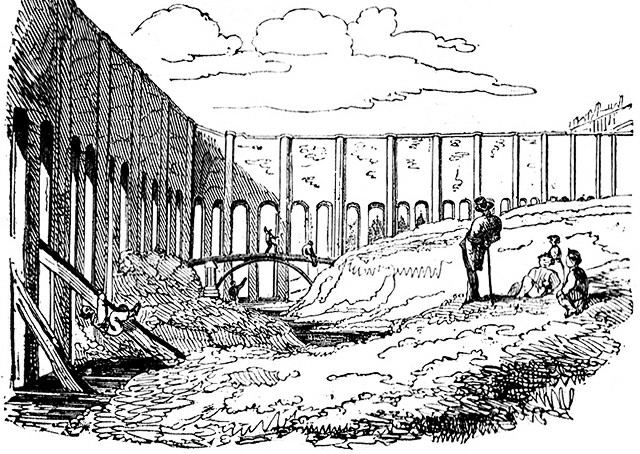

Fig.5a – Greenwood’s 1830 map showing the new course.

Looking back at Pic.1, in relation to where it was taken from on Fig.5, you may notice that the picture is taken looking south, downstream as it were, but that Pakenham Street has a rising gradient. When the prison was built the ground on the site was raised, following this the spoil from the foundation trench of the new wall was used to raise the ground level more still along the prison’s northern perimeter, along what is now Calthorpe street. Illustration.2 below, from William Hone’s Table Book, Part I (Jan 1827. col.75-76), shows very well the north-west corner of the prison site during the construction of the new wall and pictures the still undiverted River Fleet flowing about the foundations. The river bank in the foreground, on which the figures are posed, would be the original ground level. If you then consider that the foundation arches of the wall were completely covered when the trench was backfilled, it gives some idea as to how considerably the level of the ground here was raised.

Illus.2 – The new prison wall with the Fleet channel at its foundations, 1826.

The work on the new prison wall and the northern two thirds of the new sewer line took place simultaneously, during 1826. The sewer was built twelve by twelve feet, with flat sides and an arched crown and invert. When it came to the remaining third of the sewer, along the western wall of the prison, to divert the river out of the prison grounds, it was decided that the greater fall here would allow for a pipe of smaller dimensions as the incline “rendered the portion of the current through the smaller sewer equal to the larger one”(11). The remaining third of the work was of similar form but scaled down to ten feet high by nine feet wide. Pic.3 below is taken from within the last section of the twelve foot portion of the sewer, looking downstream toward the smaller lower third that diverted the river outside of the new prison walls. The branch sewer joining at the right foreground is that of Wren Street, formerly Wells Street. Being already formed when the diversion works took place it had to be suitably communicated with the new channel, which explains its high level entry to the Fleet Sewer.

Pic.3 – The southern end of the 12ft diversion channel, leading onto the 10×9 section.

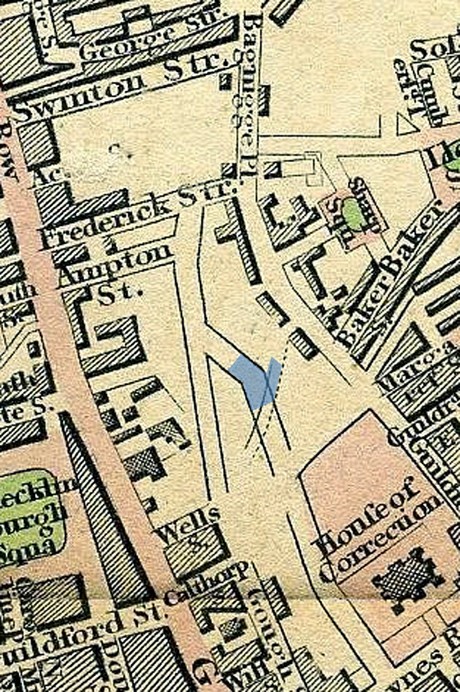

The strip of land east of the river bed, between the newly raised ground and Bagnigge Wells, had developed comparably to Pearl Crescent, with its boundaries defined by the river and the road. The difference here, besides the houses being closer in date to Bagnigge House, was that those closest to the prison site were about face to those of Pearl Crescent, with the rear walls of the houses forming part of the eastern bank of the river (as seen in Illus.3 below which depicts the scene c.1814). The natural river valley here was very prominent leading to and from the houses and this sequence of works had added a further bound of higher ground on their south side, causing them to be very peculiarly situated. The circumstance of this little cul-de-sac, marked on John Tompson’s 1803 map as Brooks Gardens, seems to have persisted for a further forty five to fifty years, as it appears still to be largely unaltered on an ordnance survey map of 1871! In the Gentleman’s Magazine of January 1855 is an article pertaining to the River Fleet, where the author’s text describes Brooks Gardens’ curious situation. “If we go to the north side of the prison, and look across a small timber-yard, we behold in a dell, some twenty or twenty-five feet beneath us, a few wretched and decayed houses, whose chimney-tops scarce reach the level of our feet. These houses must have been by the side of the stream, for they are directly on its course; but improvements have taken place around them, the soil has been artificially raised, and here they are pushed entirely aside, as if disowned by their more genteel neighbours”(12). Writing at approximately the same time, c.1855, Mr William J. Pinks also notes the significance of these dwellings in relation to the river, “The original level may still, however, be ascertained by descending a sloping way, west of the road, opposite the end of Baker Street, to some small cottages, which we presume to have formerly stood on the margin of the Fleet”(13). Fig.5 above has Brooks Gardens marked, bottom right. When the new sewer work was complete and the river’s waters had been diverted, the spoil from its cut was used to fill the five hundred foot stretch of isolated river channel still open behind Brooks Gardens and Bagnigge Wells. On a sketched plan of Bagnigge Wells, dated 1841, Anthony Crosby marks a ‘ditch’ at the eastern boundary of the gardens, where the river once ran. Though it is documented that the channel was back-filled it seems quite probable over the course of fifteen years, 1826 – 1841, that the channel’s fill had settled and a shallow drainage ditch re-established along the river’s course.

It was across the ground by Brooks Gardens that wooden pipes carried drinking water from the New River Co., as seen in Illus.3 & 3a below, crossing the River Fleet by a bridge at the south west corner of the plot. The pipes used, being hollowed out tree trunks tapered at one end and fitted one inside the other, had a life expectancy of five to fifteen years dependant largely upon the ground in which they were buried, or indeed whether they were buried at all. The water mains that crossed the river valley here were not buried and ran in four rows, alongside each other. It seems that when possible it was preferred to lay this type of pipe aboveground as it massively reduced the costs involved in locating and rectifying any leaks, of which there were many, accounting for one quarter of the water carried. Illus.3 is a reproduction by Mr F.W. Reader (1904) of an original image in the Soane Museum thought to date to c.1814. Executed looking north, the trees in the top left are those of the former western gardens of the Bagnigge Wells resort, only lost a year or so previous following Mr. Salter’s bankruptcy. The property tinted red in Illus.3 is the same property as in both Fig.5 above and Illus.3a below. The original illustration from which Mr. Reader’s was taken is said to have been commissioned to show the defective pipes at this point. Illus.3a shows the same location at seemingly the same time, taken from the Fleet’s west bank looking eastwards towards Bagnigge Wells Road; it shows the original prison wall on the far right prior to expansion of the prison grounds, while on the far left the end house of Brooks Gardens can be seen. From a description in Springs, Streams and Spas of London (Foord. 1910. pp.297) it’s fair to deduce that Illus.3a is an accompanying image to the original commission of Illus.3, though it does little to illustrate any leaks. These particular wooden mains were removed c.1815, soon after the drawings were taken, and replaced with a single iron pipe carried across the Fleet by a new bridge sited downstream some three hundred feet south west. In Illus.2 above, the bridge crossing the Fleet in the background is this secondary bridge, successor to that of Illus.3 & 3a, originally having been outside of the prison walls prior to the expansion works of 1826.

Having re-opened in 1814, by 1830 the wells resort had been under new management on three further occasions. Its clientèle was by then predominantly local residents of the lower orders of society and the venue had been transformed accordingly. The Long Room, that stretched from the main body of the house northwards along Bagnigge Wells Road, was utilised as a concert hall with an entrance located along the road. In the immediate vicinity of the resort much had changed. Land to the west of the river which once formed part of the gardens was now occupied by the yard of Thomas Cubitt, Master Builder, who also had premises in Grays Inn Road. Mr. Cubitt, along with his younger brother William, had already stamped his name on the area by the building of many of the various streets to the north and west of Bagnigge Wells, although it was to be later generations who literally put his name on the map here. By 1831 William Cubitt was at the helm of the family business and it was he who, in December of that year, put in a petition to the Commission of Sewers for the construction of a new sewer, to be eight hundred and twenty feet in length, measuring ten feet high by nine feet wide. This would be the second major work to convey the Fleet underground along this section of its course and, like the previous diversion work discussed, the drainage work here was being undertaken ahead of the development of a new public street. In fact this second series of works, in conjunction with the previous diversion, would completely remove the Fleet from sight between Frederick Street at the northern tip of our original land plot and Phoenix Place along the western boundary of the prison. The brick sewer was built during the following year, 1832, and once again the spoil from the cut of the work was used to fill the redundant section of river channel.

Fig.6 – Mogg’s 1834 map, with new junction.

Fig.7 – 1839 map showing sewer and river course.

Although work on the new street appears to have begun shortly after the completion of the sewer, both written and map records suggest that it did not near completion until 1839. In Fig.6 above, a section of Mogg’s 1834 Strangers Guide to London, we see one of the earliest mapped representations of our road junction(highlighted). Cubitt’s new roadway was named Arthur Street, later re-named Cubitt Street, and ran from Frederick Street in the north down to Wells Street, roughly following an old field/land boundary. The new sewer however did not run the entire length of Arthur Street, its course was taken to about a midway point, in line with Bagnigge Wells, and then turned south east to connect with the 1826 diversion works upon which Pakenham Street was built. The south east spur of the new sewer was also designated to be built upon, as an extension of Pakenham Street, though it did not remain as such for many years. Fig.7 above shows the site in 1839. The dashed lines of the new streets surrounding Bagnigge Wells would suggest that the area was still a work in progress. The red line shows the new underground course of the River Fleet with labels identifying the two construction periods; the paler dashed edged red line indicates the original river course, now filled in, that defined the property boundaries on either side of it. In London County Council’s Survey of London (Godfrey, 1952) it is stated that “Cubitt Street now runs where the stream reached its greatest distance from the road”(14), the road in question being King’s Cross/Bagnigge Wells Road. From Fig.7 above and the details we have covered thus far we know this not to be the case and that the stream/river was for the most part at least seventy feet east of Cubitt Street. The confusion was presumably due to Cubitt Street all but echoing the course of the river for the length of the new sewer, as can be seen in Fig.7. Their parallel trajectories are in the main resulted from the street/sewer following an old field boundary, which itself had been defined by the river, also the natural contour of the land would favour this route for an efficient drainage channel.

The marriage of the southern end of the new sewer with the 1826 works severed a two hundred foot section of the earlier tunnel, rendering it obsolete. In similar circumstances elsewhere in London, the disused section of sewer has been backfilled during the phase of works that created it and so it seems logical to expect the same to be the case here. A two hundred foot length of twelve by twelve sewer would not have been bricked up and left to decay and eventually fail, especially in a developing suburb of the Metropolis. However, I suspect it was not entirely filled, Pic.4 below is taken looking north from within the 1826 tunnel, looking towards its union with the smaller 1831 sewer. The enlarged area of the image shows a bricked up portal, approx 5ft high, located at the point where the 1826 tunnel would have continued. The simplest explanation would be that a smaller brick sewer was run through the redundant section of tunnel previous to it being filled. The form and dimensions of the portal would be consistent with those of the Holborn and Finsbury Commissions specification at that time, previous to engineer John Roe introducing the superior oval form for their branch sewers. Another possibility is that the portal is an old bricked up access passage, but its size and location mostly rule this out. The drain exploring dreamer in me would like to believe that they just left the disused section in place and formed this portal to access it, I am aware though that such a thought is about as naive as imaginings I once had of the River Fleet today being anything but a feculent waste water soup. So the first option being the most probable we can deduce that this side tunnel also became disused at some point and was filled and sealed, eliminating the route of the northern most section of the older diversion work. Over the six year period from 1826 – 1832 the quarter mile portion of the River Fleet from Frederick street in the north to Phoenix Place in the south went from being entirely open, in its natural bed, to being entirely enclosed in an artificial channel and displaced seventy feet westward, as seen in Fig.7.

Pic.4 – Union of the 1826 and 1832 works highlighting defunct mystery portal.

By 1839 the Bagnigge Wells resort, under proprietor John Hamilton, wasn’t so much hobbling along on its last legs as it was dragging itself across the muddied ground by its fingernails while trying to keep its face from falling flat in the dirt. Evening concerts were still a regular occurrence but attendance figures were pitiful, with most people preferring to frequent the tavern. The gardens had been allowed to become overgrown with nettles and the grotto and pump house were very dilapidated. The general area was by now assimilated into the great suburban sprawl and water from the wells was no longer taken on account that it was considered sullied, it was however drawn for use in the brewing process and so was still benefiting the resort in a round about kind of way. By 1841 Bagnigge Wells’ cup was well and truly dry. A portion of the boundary wall along Bagnigge Wells Road had been ‘accidentally’ knocked down in April, also causing the grotto to collapse. In June of that year, like its attendant river only nine years previous, work began to remove the decrepit remnants from view and memory. First to fall was Bagnigge House, on to which had been adjoined the Bagnigge Tavern c.1800. It is documented that a new tavern was built at the Bagnigge Wells site following the gardens closure, but I suspect this was in fact the early 1800s tavern that was retained, having been further extended to include a kitchen where the garden’s southern entrance once stood. Being of a later date and in a rather better state of repair, in comparison to Bagnigge House this tavern could certainly be considered new. The demolition work was being undertaken with a view to erecting a new terrace of housing on the cleared site and so things progressed rather swiftly, with most of the remaining buildings cleared in two to three weeks. The long room was removed to a point at which it would not hinder the construction of the new houses, but not completely removed until more than a year later. A small watercolour at the London Metropolitan Archives, dated November 1842, shows the remaining northern end of the long room with two windows still in place, while to the left of the remains is the end house of three that formed the newly erected terrace named Clarke’s Place.

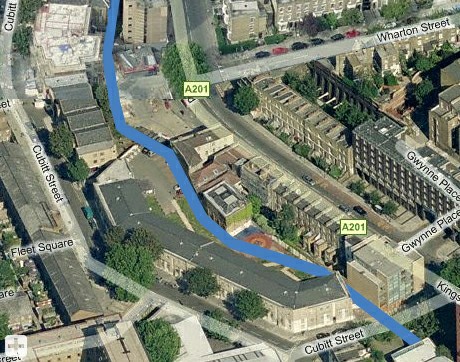

With the river through the site now entirely diverted underground, and the gardens site itself being redeveloped, you’d perhaps think that our story was complete? But the river’s influence on the further development of the area continued and continues long after it was shunted westward and buried alive. Between 1665 and 1826, while the river was open and the neighbourhood was taking shape, it was the river’s course that acted as a natural property boundary. By the time the river was no longer present these boundaries were very much established. Any new development, like that of Clarke’s Place, was undertaken respecting these existing boundaries and consequently the river’s course is still a part of the landscape today. Looking at the aerial photograph (courtesy of Google Maps) of Fig.8 below, with the property boundaries through the old Bagnigge Wells site highlighted, the course of the Fleet is still very apparent. For the sake of a little more visualisation fig.8a below shows the river’s course overlaid on a bird’s eye view of the district looking roughly northwards (courtesy of Bing Maps).

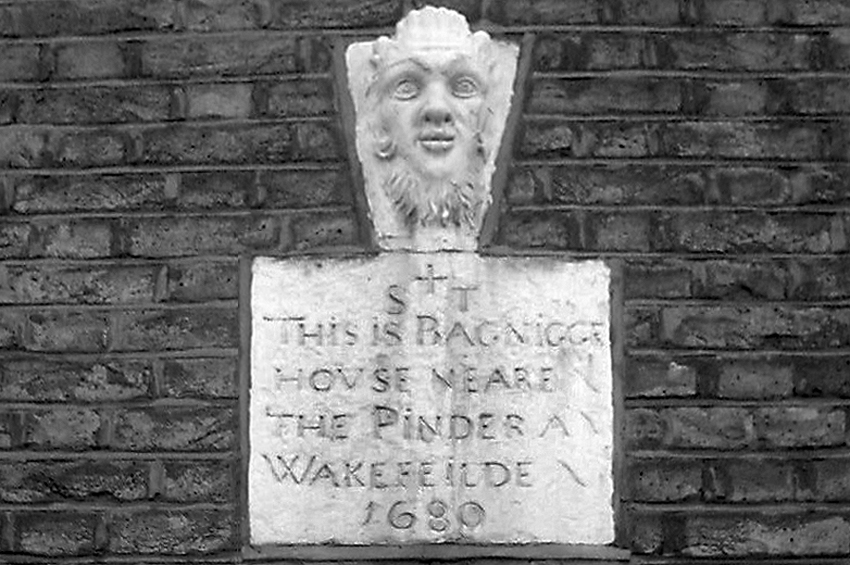

To close the book on Bagnigge Wells we should cover its very final flickering out and touch on what crumbs endure of such a significant location. In the process of extending Clarke’s Place northward on the gardens site along Bagnigge Wells Road, c.1844, the end portion of the Long Room was removed and all that then remained of the grounds themselves was a forty by eighty foot slice of land between the new housing and Chapman’s Brewery to the north. This forlorn slice of the gardens, covered with brick pieces and other demolition debris, was still bounded by its original portion of wall along the roadside frontage. Into this wall was set the eastern doorway from the road into the gardens. While the resort was still in popular use a stone inscription had been set above this doorway, having been removed from the exterior of Bagnigge House, it read “This is Bagnigge House Neare The Pinder A Wakefeilde 1680”. The Pinder of Wakefeilde being a tavern in the Gray’s Inn Road, to the west of Bagnigge Wells, which was a significant stopping point on route in and out of the city and a well known landmark. A pencil drawing in the London Metropolitan archive, signed Geo.Sidney Shepherd and dated 1849, shows the small section of wall with its doorway and inscription still existent, above the inscription a stone head is mounted which was thought to have been a later addition and not from the house.

Pic.5 – The Bagnigge House inscription mounted at the site of the former eastern doorway.

The plaque, pictured above courtesy of Diamond Geezer, is the only artefact known to survive today. It is set into the front wall of a house in King’s Cross Road (formerly Bagnigge Wells Road) and is located still at about the spot where the eastern garden doorway would have stood. So what happened to the doorway? Like the bulk of the site before it the residual slither of garden was eventually built upon, though on an ordnance survey map of 1871 it appears to have briefly formed a part of the Cubitt’s builder’s yard. Unlike its associated waterway the Bagnigge Wells resort was denied its obvious legacy amongst the city streets about its locale. Bagnigge Wells Road was re-named in 1863, presumably under the banner of progress, putting all but the last nail in the coffin that would bury the gardens. The road was given the name of King’s Cross Road, after the district of King’s Cross to which it now lead to/from. King’s Cross itself had only existed under that name for thirty three years at that time, “In 1830 Battle Bridge assumed the name of King’s Cross, from a ridiculous octagonal structure crowned by an absurd statue of George IV.”(15) The road had been known by its resort related moniker for a hundred plus years and for the majority of that time its reputation was somewhat less than rosy. Perhaps the new name was hoped to wipe out the old character, even if it was re-named after a statue that people disliked and that only stood for fifteen years. As the decision on the new road name was carried it also wiped from the map other place names whose simple etymology told of the old nature of the area. Existing rows of housing along King’s Cross Road were to be uniformly numbered for its entire length and their old terrace names, such as Brook’s Row, Field Place and Field Terrace, were abolished.

By the late nineteenth century Bagnigge Wells existed only in memory. The ‘new’ Bagnigge Wells Tavern on the corner of King’s Cross Road and Cubitt Street was the only significant presence that helped to preserve the name in the collective local consciousness. Amongst the grid of streets that then surrounded the site only one name lingered to give any intimation of its bygone days. Wells Street, to the south-west of Bagnigge Wells, was formerly a footpath across the fields from Gray’s Inn Road to the wells resort. In 1824 the Gray’s Inn Road end of the path was built up as a residential street by Messrs Cubitt and named from its obvious association. Wells Street endured for almost a century beyond the closure of the gardens, it was re-named Wren Street c.1940. More recent generations have attempted to redress the balance a little; new housing developments which stand partly on ground that formed the western gardens have been named Wells Square and Fleet Square. The New Bagnigge Wells Tavern likely lived on a little longer than Wells Street, though I can’t say for certain and have struggled to find much documentation. Two photographs taken in 1924 by the Landlord at that time, George Isaac Free, show views from the windows of the tavern’s upper floor, thus we know it at least stood until that time. It is suspected that the tavern took bomb damage during WWII and had to be torn down, speculation I hope to get to the bottom of when I get my hands on a copy of the London County Council’s Bomb Damage maps, 1939 – 1945. The property that now occupies the site of the tavern is a modern block (seen on the right below) likely built in the early 90s. It would be rather elementary to assume that the present building succeeded the tavern, and I do not believe this to be the case.

Tavern site 2010, at the corner of King’s Cross Road and Cubitt Street (click to view in Google streetview).

Before Thomas Hughes became the first proprietor of Bagnigge Wells, and before the wells themselves had been sunk, the springs upon which both depended would have drained to the river along with numerous others around about. Today the Fleet Sewer at Bagnigge Wells is a debased form of the natural river of times past, displaced from its course, with natural springs substituted by spouting cloacal tributaries of bubbling faecal brew. These counterfeit waters tickle the nose with their sulphurous odours in much the same way as the springs that preceded them. If taken, their potency would far surpass the former flows’ purgative qualities and Dr. Bevis’ recommended three pints is certainly no longer the prescribed cathartical dose. While this modern river (as seen in Pic.6 below) is far removed from its original state it is as close to Bagnigge Wells as any person can today hope to get. The extensive development of the original land plot of Fig.2 means there is little physical structure aboveground, besides the main roadway, that bridges the periods to help equate one with the other. For certain, if Mr. Touffie was instantaneously transported from the roadway in front of his property, in 1680, to the same spot in 2010 he would be as lost to his whereabouts as the river, wells and gardens of Bagnigge are to London.

Pic.6 – The Fleet Sewer at Bagnigge Wells, its purgative waters are more potent than ever the resort did deliver.

References:

1.URBAN, Sylvanus. 1813. Gentleman’s magazine and historical chronicle. London: J.B. Nichols, Son and Bentley. Volume 83: Part 2. pp.557.

2.TOMLINS, Thomas Edylne. 1858. Yseldon: Perambulation of Islington [Online], pp.160. Available: here. [Accessed 10 December 2009].

3.THORNBURY, Walter. 1878. Pentonville. In: Old and New London. Volume 2. [Online] pp. 279-289. Available: here. [Accessed 12 December 2009].

4.ASHTON, John. 1888. Chapter vii. In: The Fleet, its river, prison and marriages. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp.77

5.GODFREY, Walter H. and MARCHAM, W. McB., ed. 1952. The Calthorpe Estate. In: Survey of London: volume 24: Part 4. pp.56-69.

6.GODFREY, Walter H. and MARCHAM, W. McB., ed. 1952. The Calthorpe Estate. In: Survey of London: volume 24: Part 4. pp.56-69.

7.WHEATLEY, Henry Benjamin. 1891. London, past and present: its history, associations, and traditions. London: John Murray. volume 1. pp.87-88

8.ASHTON, John. 1888. Chapter vii. In: The Fleet, its river, prison and marriages. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp.78

9.ORD-HUME, A.W.J.G. 1978. Barrel organ: the story of the mechanical organ and its repair. London: George Allen & Unwin. pp.52.

10.LUSH, J.W. 1827. Holborn and Finsbury sewers entries of bonds and contracts 1821 – 1827. London: Holborn and finsbury Commission of sewers. London Metropolitan Archive. pp.185.

11.LAXTON, William. 1844. The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal. Volume VII. [Online] pp. 314. Available: here. [Accessed 02 February 2010].

12.WALLER, J.G. 1855. The River Fleet. In: URBAN, Sylvanus. Gentleman’s magazine and historical chronicle. [Online], 43(Jan-Jun) pp.28. Available: here. [Accessed 18 December 2009].

13.PINKS, William J. and WOOD, Edward J., ed. 1881. The History of Clerkenwell. London: Charles Herbert. pp.561.

14.GODFREY, Walter H. and MARCHAM, W. McB., ed. 1952. The Calthorpe Estate. In: Survey of London: volume 24: Part 4. pp.56-69.

15.THORNBURY, Walter. 1878. Highbury, Upper Holloway and King’s Cross. In: Old and New London: volume 2. [Online] pp.273-279. Available: here. [Accessed 25 February 2010].

Illustrations:

1.PINKS, William J. and WOOD, Edward J., ed. 1881. The History of Clerkenwell. London: Charles Herbert. pp.567.

2.HONE, William. 1827. The Table Book. Part1. London: Hunt & Clarke. col.75-76.

3.FOORD, Alfred Stanley. 1910. Springs, Streams, and Spas of London. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp.296.

3a.Uknown.

Bibliography

- ANDREWS, William. 1899. Bygone Middlesex. [Online]. Available: here. [Accessed 1 January 2010].

- ASHTON, John. 1888. The Fleet, its river, prison and marriages. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- BEW, John. 1820. London and its environs, Twelfth edition. [Online], pp.15. Available: here. [Accessed 1 January 2010].

- CLARKE. 1760. An experimental enquiry concerning Bagnigge Wells. In: The Critical Review or, Annals of Literature. [Online], pp.204-207. Available: here. [Accessed 22 December 2009].

- CLARKE, William. 1827. Bagnigge Wells. In: Every night book, or, Life after dark. [Online], pp.36. Available: here. [Accessed 22 December 2009].

- CLAYTON, Antony. 2000. Subterranean City. London: Historical Publications.

- COMMONS, The House of. 1866. Report from the Select Committee on Theatrical Licenses and Regulations. [Online], pp.301. Available: here. [Accessed 21 December 2009].

- DARLINGTON, Ida. 1970. The London Comissioners of sewers and their records. Chichester: Phillimore & Company Ltd.

- DENYER, C.H., et al. 1935. St. Pancras Through the Centuries. London: Le Play House Press.

- FOORD, Alfred Stanley. 1910. Springs, Streams, and Spas of London. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- GODFREY, Walter H. and MARCHAM, W. McB., ed. 1952. The Calthorpe Estate. In: Survey of London: volume 24: Part 4. [Online] pp.56-69. Available: here. [Accessed 15 December 2009].

- HECKETHORN, Charles W. 2009. Old London Tea Gardens. In: London Souvenirs. [Online], pp.158-161. Available: here. [Accessed 19 December 2009].

- HEMBRY, P.M., et al. 1997. Southern Spas. In: British spas from 1815 to the present: a social history. [Online], pp.104. Available: here. [Accessed 19 December 2009].

- HONE, William. 1827. The Table Book. Part1. London: Hunt & Clarke. col.75-80.

- HUGHSON, David. 1807. London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis, Volume 4. [Online]. Available: here. [Accessed 20 December 2009].

- LAXTON, William. 1844. On the forms of sewers. In: The Civil engineer and architect’s journal, Volume 7. [Online], pp.312-314. Available: here. [Accessed 12 December 2009].

- ORD-HUME, A.W.J.G. 1978. Barrel organ: the story of the mechanical organ and its repair. London: George Allen & Unwin. pp.52.

- PALMER, Samuel. 1870. St. Pancras: Being Antiquarian, Topographical, and Biographical Memoranda. [Online], pp.77-90. Available: here. [Accessed 21 December 2009].

- PINKS, William J. and WOOD, Edward J., ed. 1881. The History of Clerkenwell. London: Charles Herbert.

- PLATT, J.C. and SAUNDERS, J. 1851. Underground. In: KNIGHT, Charles, ed. London, Volumes 1-2. [Online], pp.225-240. Available: here. [Accessed 19 December 2009].

- SANDERS, Robert. 1772. The complete English traveller: or, A new survey and description of England. [Online], pp.268. Available: here. [Accessed 21 December 2009].

- SHELLEY, Henry C. 1909. Inns and Taverns of Old London. [Online], pp.162. Available: here. [Accessed 1 January 2010].

- THORNBURY, Walter. 1878. Old and New London: Volume 2. [Online]. Available: here. [Accessed 12 December 2009].

- THORNBURY, Walter. 1987. Old London: Charterhouse to Holborn. London: The Alderman Press.

- TIMBS, John. 1867. Curiosities of Clerkenwell. In: MACAULAY, James. The Leisure hour. [Online], pp.341-344, pp.366-367. Available: here. [Accessed 19 December 2009].

- TIMBS, John. 1868. Fleet River and Fleet Ditch. In: Curiosities of London. [Online], pp.346-348. Available: here. [Accessed 15 December 2009].

- TOMLINS, Thomas Edylne. 1858. Yseldon: Perambulation of Islington [Online]. Available: here. [Accessed 10 December 2009].

- URBAN, Sylvanus. 1813. Account of various mineral wells near London. In: THE Gentlemens Magazine and Historical Chronicle. [Online], 83(Jul-Dec) pp.556. Available: here. [Accessed 21 December 2009].

- WALLER, J.G. 1855. The River Fleet. In: URBAN, Sylvanus. Gentleman’s magazine and historical chronicle. [Online], 43(Jan-Jun) pp.24-32. Available: here. [Accessed 18 December 2009].

A brilliant piece of historical and archaeological detective work – only complaint it does not fill the page on my browser, and font not easy to read – query do the springs from the old spa still exist, and do they discharge dircetly into the sewer???

Thanks for the feedback Bob.

The browser and font issue is duly noted, what browser and OS are you using?

Regarding the springs which fed the wells of Bagnigge, I can’t say for certain whether they still exist. They definitely do not discharge directly (via a dedicated conduit) to the Fleet Sewer main line. At about the locations of the former wells there are various smaller local sewers which do connect to the Fleet Sewer, these exist to drain the ground, roadway (King’s Cross Road) and properties along them. Speaking generally, the upper two thirds (sides and crown) of these sewers were purposely formed so as not to be watertight, allowing groundwater in their immediate surrounds to drain into them by way of the porosity of the bricks and fissures within the mortar joints. If the springs do still exist to any extent then the chances are that their waters do drain (indirectly) to the Fleet Sewer.

Brilliant page. Very much enjoyed reading this.

@ David Brown: Thanks David, glad you enjoyed it. It’s nice to hear that it does get a read through every once in a while. 🙂

Superb piece of historical detective work with great use of a sequence of primary sources. Very impressive and I think definitely worth publishing more widely, except that it might compromise your pseudonym. And I thought the lay-out and pictures were very accessibly presented

Any chance you would put up copies / pictures / sketches of some of the other visual sources – the Crosby sketch, the Shepherd pictures and 1920s photos of the tavern?

@ Mike:

Hello Mike,

Thanks for the comment. 🙂

I wouldn’t be opposed to publishing more widely elsewhere, I’m not especially concerned about the whole anonymity thing. 🙂 I’ve added a few links in the post text, two to the photographs of views from the Bagnigge Wells tavern and one to the page for the Crosby image on the City of London’s Collage website.

I’d like to post the Crosby and Shepherd images in the text but the licence issues mean I’d have to pay a yearly sum to do so legitimately and it’s fairly expensive considering what I’d be using it for.

Hey,

I got to this from your flickr pictures, and just wanted to say thanks for going to the trouble, time, and considerable effort of posting all this information up here.. It must have taken an AGE to research, but a right rivetting read it is! And excellent photography to boot! Thanks, and please keep it up..

BOOK!

@ cactusmelba:

Thanks so much. It’s nice to hear from someone who has taken the time to read through what I know is rather a large amount of text. It did take a while to draw all the information together yes, and it took its toll in that I’ve struggled to get on with the other few similar texts I’m writing. Knowing quite the amount of work that is involved can be a little demotivating.

That said, I do hope to be posting another article along a similar theme soon.

Thanks again.

Thank you so much, what a wonderful story and thorough history. You transported me to the past and brought me up to date brick by brick. I have known this area for many years, but had no idea about it’s history, fascinating and enjoyable. I came across your website after seeing the name Bagnigge Wells mentioned as a distant relatives place of birth and wondered where it was.

Thanks again

Vanda

@ Vanda:

Glad to hear you enjoyed the article. There isn’t a great deal of in depth information to be found online regarding the general neighbourhood, I’m happy to have provided a little.

Great article JD, the research that most have gone into this boggles the mind. I’m currently en route to London so was most pleased to find to a decent read to keep myself from boredom.

Cheers,

CJ

Wonderful page and exhaustively researched. The very anonymity of this area of King’s Cross makes reading your history all the more alluring and fascinating. This is an area steeped in romantic melancholy, charting a place frequented by all manner of people and social classes over the years, now all but lost save the gargoyle behind the criminally positioned bus top. Thank you for this. The maps linking the site of the Wells to the site of the tile kilns and other landmarks is especially appreciated as I had wanted to get my head around this.

Many thanks again.

Alex, 35 (graphic designer formerly working in Collier Street, King’s Cross)

@ Alex Ingr

Thanks so much for the comment. I’m always genuinely am happy to hear that this article does get read once in a while. It did take me a while to put together and did involve quite some research, as you kindly acknowledged. Unfortunately with this I did set myself a benchmark that these days I struggle to find time to meet, so a follow up piece is VERY slow in coming. I am still writing another similar article about the Fleet, focused on it’s course downstream from Bagnigge Wells, from Ray Street to Holborn Bridge (Holborn Viaduct). There’s a bit still to write and images, maps and plans to put together, but I’ll get there. 🙂 Thanks again.

@ concreteJungle

Thank you kindly Sir. As I’ve mentioned already in these comments, I think writing this article crushed my literary mojo somewhat and I’ve struggled ever since to find time to put something worthwhile together. I’m glad I wrote it though, there really wasn’t anything much out there about this neighborhood and the Fleet’s course through it.

Did you have fun in the Metropolis?

I’m not surprised you don’t publish many articles like this, they are hardly something one can churn out.

Unfortunately I find my self visiting the Big Smoke for work far more than pleasure. As it happens I think the Fleet goes right past my office in Holborn though. Every time I walk past the vents in the road and helpfully labelled lids (!) I find myself daydreaming about donning the waders and finding out for sure.

I look forward to the next installment, whenever that maybe!

Cheers,

CJ

Brilliant!

Thanks to Lee jackson who brought this to my attention.

I used to live in Frederick Street in the late 80’s; that

90’s looking building you mentioned on the next corner

down replaced a petrol (Shell I think) station and some

Georgian buildings (one with a horse yard) I think but

I am not sure. We’d often buy snacks from the garage.

I was very surprised to see it gone on a wander around

there some time ago. There used to be a tiny shop called

The Hat Box close to the other corner Kings Cross Road/

Frederick Street.

Last time I looked it was hard to see

what was going on there. I heard when they were cutting

(and covering in places) the tube through this area

the was a collapse I wonder if the ancient river was

the cause?

Echoing what everyone else said great post and I look

forward to the sequel 🙂

Fantastic read. I appreciate the hard work you have put into this in order to create an entertaining and informative document.

Thank you for writing this fascinating article! I had never heard of Bagnigge until I read this page but lived for a year close by in Wren Street (formerly Wells Street) as a student. I’ve been interested in the Fleet for years (I was a geography student) but had no idea I once lived within metres of its present course! Thanks again for your superb research and hard work.

Let me join the plethora of messages of gratitude and thank you for putting together such a fascinating article. I live on Cubitt Street – pretty much above the path of the Fleet.

p.s A few years ago the basement flats were flooded from a leak caused by an overflow from the Fleet. Its lurking presence seems perpetually mysterious….

Hi Jondoe

Great piece of writing there! Very interesting – and more importantly very useful!

Re: the 200foot abandoned length of sewer. Presumably this would be just north of the junction of Cubitt St & Pakenham Street, and project the modern flats that stand where the southern parts of the Gardens would have been? Course it’s still there! Filled with giant blind rats I shouldn’t wonder 🙂

I think I’ve spotted a minor typo though : “In Illus.1 above, the bridge crossing the Fleet in the background is this secondary bridge…” – should this be referring to illus. 2, the foundations for the Correction House?

Muchly looking forward to the next piece further downstream!

Cheers,

MD

Hi MD,

Thanks for the comments and the heads up on the typo (amended).

The ‘abandoned’ section would indeed be situated where you say, I’m pretty sure it’s now a realm of hidden chalybeate caverns of wonder, where disease and ailments are consigned to history.

I’m probably looking forward to finishing the next part more than anyone . . . . :/

Although I have absolutely no connection to the above location (or indeed England itself) I thoroughly enjoyed the article. Well written and very informative.

Thank you,

A virtual visitor from Ohio, USA.

Wow…this was truly inspiring. I just stumbled across this site and I am very impressed by the research put into this article.

Can’t wait to read some more. Thank you.

Best Regards.

-Caveman 001-

I like to walk the route of the fleet from work in the city back to St Pancras. It fascinates me see the way natural geographical features have been incorporated into the built-up area and I love the history of the development of the site.

This article is well researched and perfectly readable. I really appreciate the time you’ve gone to collecting this information together that makes the history so much more accessible. It makes a lot of difference to me to be able to picture in my mind the river course and the original land levels as I walk along the present-day roads. Thanks and well done!

Thank you John. Nice to know others who share my fascination appreciate the effort put into uncovering this section of the Fleet’s course.

Thank you for a fascinating article which I have linked to my blog. I am exploring London with Bradshaw’s Hand Book to London, 1862, and this has been very helpful and interesting

You’re welcome, glad you enjoyed it. I’ll have to hop on over to take a look at your blog, sounds like just my cup of tea. 🙂

Whilst researching my family history. My great great-grandmothers family (Hannah Evans – Father John Evans) lived at 2 Brooks Gardens. The address appears a number of times re: births, marriages and deaths. It appears they lived in the house from 1840’s. Hannah married George French, and lived in the house with her 4 children. On becoming a widow at the age of 36 she married Mr Seaward and gave birth to twins in 1874 (my great grandmother). The last mention of the address is the 1881 census. The families were large and poor. My families occupations range from Skin Merchant, errand boy, labourers.

Hello Vivian, Thanks for your reply. That’s fascinating stuff and nice to have that insight into the lives of people who lived in the locale at the time. Amazing to hear that the address was still extant during the 1881 census too.

A fascinating read covering two of my interests – underground and history! Just wanted to say thanks for the no doubt huge effort that went into researching this – brilliant stuff.

To repeat others before me – Fantastic read. I appreciate the hard work you have put into this in order to create an entertaining and informative document.

It’a an area I can walk thru in my lunch time (I work in Naoroji Street). I had been exploring Gwynne Place, then Googled the name and came upon Sub Urban.

Are the remnants of a peripheral wall around the north of the Mount Pleasant Post Office site (in Calthorpe Street) remains from the prison ?

Hello Howard, Thanks for taking the time to read the article. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the low wall on Calthorpe street is remnants of the prison wall, at the very least I imagine it’s built on the same footings.

Fantastic read, I’ve been through your whole site and have nothing but admiration for your dedication, and jealousy for the amazing places you’ve been in and recorded. As a construction professional, I’m awestruck by what previous generations achieved, and it’s continuing efficacy (the Thames Tideway excluded lol). thanks again 🙂

Howard, you are quite correct – the effort that John Doe puts into his research is, I believe, legendary and universally appreciated amongst sub-urban historians, particularly those of a Fleety-bent.

I’m sure you know already, so pardon me – but you work in a street surrounded by such history. River Street, Amwell Street and Sadler’s Wells all nearby recalling not-quite-yet forgotten watercourses and springs. And Merlin Street – recalling the old Merlin’s Cave tea-shop. An image-search using the engine of your choice for “Merlin’s Cave tea shop” may yield some interesting finds.

Next time you’re on a lunch-time stroll, and wish to investigate this most wonderful of rivers further, you might find this map handy:

http://tinyurl.com/fleet-map

I must say though that I’m not altogether convinced that low wall on Calthorpe Street is the original House of Correction wall. I’d love to be wrong though I hasten to add but as I recall the brick work just looks in to good a condition. I shall look again next time I’m passing.

JMR

Incdidentally, did you see the recent episode of New Tricks in which the River Fleet played a starring role?

Wow what a read. I have been researching the River Fleet for 3-4 years and not found this til now – shame on me. Well done on the incredible research. I find terrific value in the orientations of the brick tunnels, many thanks.

Cant believe Dave Brown found this 4 years ago….

It is now 2016 and your work is still a most interesting piece of research. I was following the Pindar of Wakefield/Civil War Pindar Fort route and fund the Bagnigge House link.

Thank you very much.

Thank you Selwyn. If only I could find the time and motivation to turn out some more of the same . . . one day, one day.

Jondoe – do you have any other writings (historical or otherwise) uploaded anywhere else on the Internet ?

Thank you so much – I have really enjoyed your discussion and analysis on the Bagnigge wells and surround. I cycle arround here on my way to work and imagined that I follow the River Fleet , atleast to some extent . Also , I am particularly interested in Dickensian London – I work in the area and am always looking for locations mentioned in say Oliver Twist (e.g Safron Hill and the river fleet ) , the Pickwick Papers (Goswell Road) . Sometimes I wish I could be transported back to say 1830 just to take a look arround – and experience these places for real .

Hi Leon, Thanks for your thoughts. If you do figure how to make a day trip to the 1830s, let me know, I’d join you in a heartbeat. I’ve just recently picked up an article I started to write way too long ago to think about. It covers the area from the north of Saffron Hill down to Holborn Bridge (Viaduct), in much the same vein as the Bagnigge piece.

Fascinating. I love the whole story if pleasure gardens. However I stumbled across this article because I was looking for information on George Lines who had a rocking Horse workshop in Bagnigge Wells in the second half of the 19th century (I think the company moved by about 1880?) I wonder did you come across any reference to that at all?

Hello Helene, Thanks for your reply and interest. I’m afraid I didn’t come across any reference to George Lines in my research for the wells article. Sorry.

Hi. Thanks for this article – most impressively researched, I can’t imagine the hours you put into this.

I have walked the course of the Fleet several times now, the last last being last Friday 25 Jan, where I came across works going on in Calthorpe St.

The works have exposed a length of 3ft diameter iron pipe (looks like iron anyway). The works extend from the junction with Phoenix Place and extend a good 20 or 30 yards towards Kings Cross Rd along the south side of Calthorpe St. I am hoping I have just seen the Fleet? Any thoughts? I have a picture but not sure if I can add pictures to the comments.

Hi James! Thanks for your comment. It was rather a long slog to finish this particular article yes, so much so it all but killed off my writing. I saw those works you mention the other day or at least associated ones. It sounds like the pipe you saw may have been water main/supply related, although that’s pretty large. It could have been a Fleet Sewer branch, there definitely are a few that join in that vicinity, though they tend to be brick built 4ft diameter affairs thereabouts. It sounds like you’re a bit of a Fleet aficionado yourself?

Hi. Thanks for your reply. All makes sense as the pipe was running at right angles to the Fleet. Yes I do enjoy my Fleet study and walks. I am pushing my old mum in a wheelchair from the Vale of Health to Blackfriars 2nd March along the Fleet route. She used to live in Southampton rd, Gospel Oak so knows Fleet rd well. I will have help but it will take us all day taking in all the history along the way.

What a superb piece of research and writing! Brilliantly scholarly and intrepid. It’s by far the best piece of writing I’ve read, amongst the several books and websites I’ve read. I bookmarked and skimmed this piece a few years ago when I moved to Calthorpe street, but have only just given it my full attention. You have addressed a great many of the queries that were independently forming in my mind as to the precise course, and the diversions.

A couple of further questions though:

How is Bagnigge pronounced? Is it related to the French ‘baigner’ perhaps? Were there any allusions to swimming or bathing? And the …nigge? I’ve always said it like siege or liege.

I’ve noticed that immediately outside the main door of that modern building on the corner of Cubitts st, and Kings Cross Road, there is a constantly burbling drain, but if the main sewer was shifted eastwards, what then is this? The noise indicates a flow at least as voluminous as say the one adjacent to the Prince Albert On Royal College Street.

I wonder if you’ve noticed any signs or remnants of the river or sewer during these vast new residential construction works immediately to the south by Postmark and Blue Sky Buildings? I often looked through the fences at the wasteland that is now being built upon for indications of the river, and wondered if the foxes resident there could tell me more. It’s course across Mt Pleasant at the cobbled low point west of The Apple Tree seems clear, but behind that up to Calthorpe St. has not been clear, and is now completely occluded.

Thanks again for a fantastic piece.

Hi Ben!

Firstly, I’m so pleased that this article is still getting the occasional read through by interested parties. It became something of a slog to complete so it’s great to hear it’s still getting some appreciation ten years on.

The pronunciation seems to be subject to interpretation. I’ve always pronounced the nigge as nij, as in carnage, but I’ve heard it pronounced niyj, nig, and neej. The drain you mention at the junction of King’s Cross Road and Cubitt Street is most likely a small (relatively speaking) branch sewer as the Fleet main line is definitely running to the east. The acoustics are quite something in a confined space when a head of water is barreling down a small tunnel/pipe. So if it’s joining the fleet from the north-east say, the fall into the Fleet valley there would have it traveling at quite a pace. There’s definitely nothing major at that street junction.

I’ve wondered the same about the Postmark site. I’ve haven’t caught any glimpses of anything but they would have encountered the remnants of the old course there for sure, even the existing smaller branch sewer that was run along the former river course there would have been something they’d have had to contend with. I’d be very interested to hear what the groundwater situation was through there too.

I really must pick up the many various half-finished pieces that continue on from this. It would be nice to finally put a few of them to bed.

Tim

hello,

I’ve only just come across the name ‘Bagnigge Wells’ (in an address on a death cert from 1855) so googled it – and have really enjoyed your article. Having had no idea of its existence before, I now want to visit, even if it’s only to imagine what might lie beneath my feet!

Thank you!

Hello mate,

Like you, I’m obsessed with the springs of the fleet – but unlike you I don’t put in the amazing hours of research that you have – what an absolute star you are.

I also think the way you’ve shown and described the original topography and aspect of Bagnigge is exactly what I hoped it would be in my head.

I’ve got a couple of questions if that’s ok?

I remember reading somewhere online about the original depth of the Fleet Valley at the bottom of the junction with Great Percy Street which gave a depth in ft – it was an extraordinary stat which showed how deep the river cut through it’s valley. I live in Clerkenwell and I can’t envisage how deep a chasm this valley would have originally been before tube, and general uplifting of the land. I found a paragraph on British History online which gave the original street level at Rosebury Avenue junction:

“In 1855,” says Mr. Timbs, “the valley of the Fleet, from Coppice Row to Farringdon Street, was cleared of many old and decaying dwellings, many of a date anterior to the Fire of London. From Coppice Row a fine view of St. Paul’s Cathedral was opened by the removal of these buildings. ‘In making the excavation,’ says a writer in the Builder, ‘for the great sewer which now conveys from view the Fleet Ditch, at a depth of about thirteen feet below the surface in Ray Street, near the corner of Little Saffron Hill, the workmen came upon the pavement of an old street, consisting of very large blocks of ragstone of irregular shape. An examination of the paving-stones showed that the street had been well used.”

But it was the Percy Circus valley I can’t find – it basically would have been a chasm. What is your thinking on this?

Also I have tried to find out what happens to springs when they are disturbed – do they just stop flowing? Does the water go somewhere else?

And a cheeky final one – what are your thoughts on the water source of the Clerk’s Well? In my heart I want it to be from it’s original source but in my head I doubt it 🙁

Asking you as the internet just doesn’t seem to Know. If you would ever like a pint in a lovely pub to chat about the waters of Clerkenwell, my friend and I would gladly entertain you!

This is such a great blog – you are a hero!

Dan

Hello Dan,

Firstly, thank you for the kind words in appreciation of the essay, I’m genuinely grateful to hear that it is still being read and enjoyed. Secondly, my apologies for the delayed reply, life has gotten rather busy since the care free days of 2009-10; however, the lack of free time hasn’t quelled my passion for the Fleet, or London’s drainage in general. My interest has always primarily been the underground drainage networks, but natural watercourses form part of that and the Fleet just hooked me in a way that none of north London’s other Thames tributaries quite did. It always frustrated me a little when reading texts about ‘the Fleet’ that they lacked much detail about the river itself and its circumstance and often focussed heavily on the locales and events occurring along its banks. Certainly that is a part of the history of the river and in many cases directly affected its course and its fate and it may sound an odd thing to say, considering this Bagnigge Wells text, but I always tried to keep the Fleet the primary focus, as I know too well the ease with which you can find yourself reeling off 1000s of words without much mention of the river.

As I understand, the natural river course swung significantly south around what would become the end of Great Percy Street and given the topography of the Thames valley you can imagine the Fleet was quite a rapidly moving body of water about that point. It must have cut quite a trench through there! I haven’t studied that area in great detail and a cursory search online couldn’t turn up anything specific to depths thereabouts, as you mention. Prior to those streets being developed the east bank was open ground in fairly recent history, I believe it was some sort of allotments/gardens? Myddelton Gardens? There’s quite a collection of drawings and paintings around Bagnigge wells c.1810 – 1840 and (trusting they captured a true representation of the place) they show a notably steep rise each side of the road. There was also some man-made differences in levels due to the extraction of clay for tile making along the road there. I’m not sure if it extended up quite as far as Great Percy Street, but certainly there was a notable difference in levels between Bagnigge Wells Road and Granville Square as a result.

If there’s anything I’ve seen from spending many an hour wandering through sewers it’s that water will always find a way! All along the Fleet sewer, but particularly through Clerkenwell and the lower Fleet valley, there are countless points where groundwater penetrates the brickwork. If springs are still flowing, they will no doubt find their way to the rivers they once did, no matter what obstacles have been put in their path. There’s quite a few ‘spouts’ along King’s Cross Road, just south of what would have been the St. Chad’s Well site. Constant flows of cold, clear water burst through the brickwork at about head height and are very obviously different in nature to the water flowing through the sewer itself.

I think there’s every possibility that the source(s) of the Clerk’s well still exist, but I’m onboard with your doubts that they likely do not fed the well itself any longer. There’s been sooooo much development in the area, particularly below ground, that I suspect the disturbances would have had some impact . . . that said it is at least east of some of the more significant civil engineering works.

I know I’ve mentioned this a few times previously in replies to comments on this post, but I STILL have an 80% complete draft of a further post that continues to track the Fleet’s course downstream of Warner street. I do intend to actually finish it one day, although jumping back into a writing style of ten years prior may prove tricky.

A pint sounds great btw . . . just need to find some time. ?